3| Cloud Firestore

Realtime streams, advanced querying, and when to denormalize.

Up until this point we’ve been covering Firebase from a general point of view. From here on out, we’ll be getting really specific and focusing on individual products and their features.

We saw that with security it’s really important to have authentication figured out. But! We’re going to start with the database, because well that’s the fun part.

What is Firestore?

Firestore is a NoSQL document database, with realtime and offline capabilities. Firestore is designed to reduce if not eliminate slow queries. In fact, if you manage to write a slow query with Firestore it’s likely because you’re downloading too many documents at once. With Firestore you can query for data, and receive updates within 500ms every time a data updates within the database.

Firestore is extremely powerful, but there’s a bit of a perspective shift if you’re coming from a SQL background.

SQL and NoSQL

Many developers come to NoSQL with at least some SQL experience. They are used to a world of schemas, normalization, joins, and rich querying features. NoSQL tends to be a bit of jarring experience at first because it has different priorities. SQL prioritizes having data in a uniform and distinct model.

This data model is built through tables. You can think of tables in two dimensions: rows and columns. Rows are a single record or object within the table. Columns are the properties on that object. Columns provide a rigid but high level of integrity to your data structure.

This table has uniform schema that all records must follow. This gives us a high amount of integrity within the data model at the cost of making variants of this record. You can’t add a single column onto a single row. If a new column is created, every row gets that column, even if the value is just null. Let’s say we wanted to add another column to this tbl_expenses table: approval.

Expenses can be personal so this column may not make sense for every column. For those cases how do we fill the column? Do we make it false? Well, that might communicate that the manager didn’t approve a personal charge and it could also accidentally end up a query looking for all unapproved expenses. How about making it null? This value is supposed to be a boolean, but if we make it nullable, it can have three states. If you can have three states, is it really a boolean?

Usually in those cases you would have to create another table such as: tbl_business_expenses. Now, to get a list of personal and buisness expenses back you’d have to write a query.

-- Union expenses with business expenses

SELECT id, cost, date, uid

FROM tbl_expenses

WHERE uid = 'david_123'

UNION

SELECT id, cost, date, uid

FROM tbl_business_expenses

WHERE uid = 'david_123'The advantage here is that the data integrity is high, however it’s at the cost the read time. Anytime you have to write a JOIN or some other clause you are tacking on the time to complete the query. In simple queries this isn’t a big deal, but as data models grow more complicated the queries do as well. If you aren’t careful, you can end up with a 7 way INNER JOIN and just to get a list of expenses.

A query like that can be rather slow. If this kind of query is one of the most important aspects of your site, it needs to be fast, even as more and more records are added to the database. As the database needs to scale, you’ll need to put it on beefier and beefier machines, this is known as scaling vertically.

Reads over Writes

NoSQL databases don’t care as much about uniformity and definitely not as much about having a distinct model. What Firestore priorities is fast reads. In many applications it’s common to have more reads than writes. Take a second and think about some of the most common apps and sites in your life. Now think about how much more you consume the content from them versus write updates to them. Even if you are an avid poster, it’s still likely that you scroll through your feed more.

In the Firestore world, we’re going to be shifting away from data normalization and strong distinctive models. What we’ll get in return are blazing fast queries with realtime streaming. In addition, as your database scales up to support more data it can be distributed across several machines to handle the work behind the scenes. This concept is known as scaling horizontally and it’s how Firestore scales up automatically for you.

With all that out of the way, let’s see how you store and model data in Firestore.

Tables -> Collections

If SQL databases use tables to structure data, what do NoSQL database use? Well, in Firestore’s case data is stored in a hierarchical folder like structure using collections and documents.

Collections are really just a concept for documents all stored at a similar path name. All data within Firestore is stored in documents.

Rows -> Documents

Firestore consists of documents, which are like objects. They’re not just basic JSON objects, they can store complex types of data like binary data, references to other documents, timestamps, geo-coordinates, and so on and so forth. Now in SQL all rows had to have the same columns. But that’s not the case in NoSQL every document can have whatever structure it wants.

Each document can be totally different from the other if you want. That’s usually not the case in practice, but you have total flexibility at the database level. You can lock down the schema with security rules, but we’ll get into that later.

Retrieving data

With SQL you think about retrieving data in terms of queries. While that is still true here, you should primarily think about data in terms of locations with path names. In the JavaScript SDK we call this a reference.

References

Documents and collections are identified by a unique path, to refer to this location you create a reference.

import { collection, doc } from 'firebase/firestore';

const usersCollectionReference = collection(db, 'users');

// or for short

const usersCol = collection(db, 'users');

// get a single user

const userDoc = doc(db, 'users/david');Both of those references will allow you to get all of the data at that location. For collections, we can query to restrict the result set down a bit more. For single documents, you retrieve the whole document so there’s no querying needed.

Using the Emulator

Firestore has a fully functional offline emulator for development and CI/CD environments. In the last section we set up our project to run against the emulators. But as a review, you setup and run the emulators with the Firebase CLI and then use the JavaScript SDK to connect out to the emulator.

import { initializeApp } from 'firebase/app';

import { getFirestore, connectFirestoreEmulator } from 'firebase/firestore';

import { config } from './config';

const firebaseApp = initializeApp(config.firebase);

const firestore = getFirestore(firebaseApp);

if(location.hostname === 'localhost') {

connectFirestoreEmulator(firestore, 'localhost', 8080);

}Whenever you are on running on localhost your app won’t connect out to production services.

onSnapshot()

With a reference made, we have a decision to make. Do we want to get the data one time, or do we want the realtime synchronized data state every time there’s an update at that location? The realtime option sounds fun, so let’s do that first.

import { onSnapshot } from 'firebase/firestore';

onSnapshot(userDoc, snapshot => {

console.log(snapshot);

});

onSnapshot(usersCol, snapshot => {

console.log(snapshot);

});The onSnapshot() function takes in either a collection or document reference. It returns the state of the data in the callback function and will fire again for any updates that occur at that location. What you notice too is that it doesn’t return the data directly. It returns an object called a snapshot. A snapshot is an object that contains the data and a lot of important information about its state as well. We’ll get into the other info in a bit, but to get the actual data, you tap into the data function.

onSnapshot(userDoc, snapshot => {

// this one one doc

console.log(snapshot);

// this is the data

console.log(snapshot.data());

});

onSnapshot(usersCol, snapshot => {

// this is an array of docs

console.log(snapshot.docs);

// you can iterate through and map what you need

console.log(snapshot.docs.map(d => d.data()));

});What makes this realtime? Well, whenever an update occurs at this location it will re-fire this callback. For example:

onSnapshot(userDoc, snapshot => {

console.log(snapshot.data());

// First time: "David"

// Second time: "David!"

});

updateDoc(userDoc, { name: 'David!' });This isn’t just local, this callback fires across all connected devices.

Writing data

Speaking of updates. What we see right here is one of the several update functions or as we call them mutation functions.

setDoc()

In Firestore calling setDoc() is considered a “destructive” operation. It will overwrite any data at that given path with the new data provided.

const davidDoc = doc(firestore, 'users/david_123');

setDoc(davidDoc, { name: 'David' });For the instances where you want to granularly update a document, you can use another function.

updateDoc()

The updateDoc() function can take in a partial set of data and apply that update to an existing document.

const davidDoc = doc(firestore, 'users/david_123');

updateDoc(davidDoc, { highscore: 82 });It’s important to note that updateDoc() will fail if the document does not already exist. In the case where you can’t be certain if a document exists but you don’t want to perform a desctructive set, you can merge the update.

const newDoc = doc(firestore, 'users/new_user_maybe');

setDoc(newDoc, { name: 'Darla' }, { merge: true });This will create a new document if needed and if the document exists, it will only update with the data provided. It’s the best of both worlds.

deleteDoc()

Deleting a document is fairly straighfoward.

const davidDoc = doc(firestore, 'users/david_123');

deleteDoc(davidDoc);Generating Ids

Now that’s for single documents. What about adding new items to a collection? Do you have to think of a new ID every time?

// Don't want to have to name everthing? Good!

const someDoc = doc(firestore, 'users/some-name');

const usersCol = collection(firestore, 'users');

// Generated IDs!

addDoc(usersCol, { name: 'Darla' });The addDoc() function will create a document reference behind the scenes, assign it a generated id, and then data is sent to the server. What if you need access to this generated ID before you send its data off to the server?

// The ids are generated locally as well

const newDoc = doc(userCol);

console.log(newDoc.id); // generated id, no data sent to the server

setDoc(newDoc, { name: 'Fiona' }); // Now it's sent to the serverGenerated Ids in Firestore are created on the client. By creating an empty named child document reference from a collection reference, it will automatically assign it an generated id. From there you can use that id for whatever you need before sending data up to the server.

Timestamps

One of the tricky aspects with client devices are dates and timestamps. Firestore allows you to set dates on documents.

const newDoc = doc(firestore, 'marathon_results/david_123');

// Imagine this runs automatically when a runner crosses the finish line

setDoc(newDoc, {

name: 'David',

finishedAt: new Date() // Something like: '5/1/2022 9:32:12 EDT'

});In this example, this user document is added with an finishedAt field set to the device date. But it’s only the current date based on that machine. Imagine if this was an app one the user’s phone that ran this code when they crossed the finish line. The user could change their device settings and set the world record if they wanted to. Instead, we rarely use local dates for timestamps and we use value to tell Firestore to apply a time on the server.

const newDoc = doc(firestore, 'marathon_results/david_123');

// Imagine this runs automatically when a runner crosses the finish line

setDoc(newDoc, {

name: 'David',

finishedAt: serverTimestamp()

});This function acts as a placeholder on the client that tells Firestore to apply the time when reaching the server.

Incrementing values

One of the most common tasks with data is just simply incrementing and decrementing values. The math is simple, but the edge cases in a realtime system can be really tricky.

- You first need to know the state of the data

- Then you need to add or substract from the value

- Then you update the new score

But what happens if that value was updated during that process? The new value will likely be wrong. Firestore has a few ways of handling these types of updates, but the most convienent are the increment() and decrement() functions.

const davidScoreDoc = doc(firestore, 'scores/david_123');

const darlaScoreDoc = doc(firestore, 'scores/darla_999');

updateDoc(davidScoreDoc, {

score: decrement(10),

})

updateDoc(darlaScoreDoc, {

score: increment(100),

})The functions ensure that the incrementing and decrementing operations happen the latest value in the database. It’s important to note that these functions can only work reliably if ran at most once per second. If you need updates faster than that you can use a solution called a distributed counter. But that’s for another class.

Now there’s one thing you should notice here. We’re making updates to the server, but nowhere are we awaiting the result of the update. It’s still an async operation, but why aren’t we awaiting the result?

Synchronization

I’m about to dive into one of the core principles of the Firebase SDKs: unidirectional data-flow. If you’ve ever used React, Redux, or something similar you’ll be familiar with this concept.

Redux-like updates

In a CRUD like system you’ll make a request to a server to create a resource and get the result back in the response.

const response = await fetch('/api/users', { method: 'POST', body: bodyData });

const newUser = await response.json();

console.log(newUser.id);During this process we’re waiting on the server response to continue. We’re not locking up the main thread obviously, but the response is what makes the app function. What if we could instantly get the response back? That’s what happens with listeners in Firestore.

onSnapshot(userDoc, snapshot => {

const user = snapshot.data();

console.log(data);

// First time: { name: "David" }

// Second time: { name: "David!" }

});

updateDoc(userDoc, { name: 'David!' });This is a similar example to what we saw before. But notice that there is no await or even a result returned from updateDoc(). Calling updateDoc() triggers an update to onSnapshot() and that’s where we get the update or new resource. Now you might be asking, can I await the result of mutation function? Yes, you can, but it’s rare that you’d want to do it. Why? Let’s take a look.

onSnapshot(userDoc, snapshot => {

const user = snapshot.data();

console.log(data);

// First time: { name: "David" }

// Second time: { name: "David!" }

});

const result = await updateDoc(userDoc, { name: 'David!' });

console.log(result); // { id, path, path, parent }In this example we await the updateDoc() function. This is like a server receipt that the operation was received and completed. It returns a promise of a document reference, but not the data. You can get the newly created ID, but as we saw before that ID is created on the client. If you need it, you can create a blank child document and then use setDoc() instead. So we don’t need to use await to get the ID. What about if we just want to be really certain that the object was sent to the server? You can do that and in some cases it might be necessary. However, it’s important to realize what that does.

Firestore is capable of working while offline. It synchronizes changes within IndexedDB, so if your app loses connection, it keeps working against the it’s local cache of data. However, if you are using await to get the result of mutation functions, you’re going to have to wait until the app regains connection for them to resolve. Remember, it’s a receipt from the server. This potentially can make your app unresponsive while offline.

const App = () => {

const store = useStore();

const state = store.getState();

// First render: { users: [] }

// Second render: { users: [ { name: 'David' } ] };

// Trigger a re-render

store.dispatch({ type: 'USER_ADDED', data: { name: 'David' }});

return (

// …

);

}I strongly recommend not using await for mutation functions and getting the result back in onSnapshot() function. If you use Redux, you can think of this as “dispatching” changes to the store.

Don’t think in terms of “request/response”, think in terms of triggering or dispatching updates to a central store. This is especially useful when dealing with collections.

Document change types

Remember how I told you that the Snapshot was really useful? Get used to me saying that, because I’m going to be saying it often. Rather than just getting the data outright, you can also see the changes happening since the listener was created using snapshot.docChanges.

onSnapshot(usersCol, snapshot => {

console.log(snapshot.docChanges[0]);

// { type: 'added', doc: {}, oldIndex: -1, newIndex: 1 }

// Create an object indexed by changes

const changes = snapshot.docChanges.reduce((acc, curr) => {

acc[curr.type] = curr;

}, { added: [], modified: [], removed: [] });

console.log(changes);

// { added: [{ type: 'added', doc: {} … }], modified: [], removed: [] }

});

addDoc(usersCol, { name: 'David!' });In this case when we add a new user it will fire the callback of onSnapshot(), and from there we can tap into the docChanges array. This tells us what changes have happened since the listener was created. We can see the type of change ("added", "removed", and "modified"), the document itself, and the old and new indexes of the array position. This makes it really easy to implement reordering and animations to show updates to the data. When an item is added, it can flash in green, when it’s updated it can flash yellow, and then red and fade out when deleted. A lot of framework libraries in my experience have made reordering plug-and-play. Angular Material deserves a shout out here. The DragList object works perfectly with these changes.

And that’s not all you can get from a Snapshot. I don’t know if I said this, but it’s really useful.

The offline cache

Firestore is designed to work even when the client loses connection. When data is downloaded using the SDK, it is stored in a cache that is backed by IndexedDB. You don’t have to write your code in an “offline” and “online” modes either. Firestore will continue to fire events and work. Once the connection is regained, Firestore will synchronize the changes back to the server. The only code change you need to make is to enable the caching behavior.

import { getFirestore, enableMultiTabIndexedDbPersistence } from 'firebase/firestore';

enableMultiTabIndexedDbPersistence(getFirestore());Firestore actually has two caching behaviors: single tab and multi tab. This function sets up multitab synchronization, which enables all tabs to synchronize from the same cache. If you’ve ever opened up two tabs of an offline web app, you’ll like have ran into a message saying offline is only available in one tab. With Firestore, you don’t have that problem.

Snapshot metadata

For the most part the cache is hidden away from you. However, you do have access to some important cache information when dealing with a Snapshot, like its metadata.

onSnapshot(userDoc, snapshot => {

console.log(snapshot.data());

// First time: { name: "David" }

// Second time: { name: "David!" }

console.log(snapshot.metadata);

// Very first time, data is loaded:

// { fromCache: false, hasPendingWrite: false }

// Second time, data is updated locally:

// { fromCache: true, hasPendingWrite: true }

});

updateDoc(userDoc, { name: 'David!' });This tells you information about whether the data has been sent to the server and the snapshot was delivered from Firestore’s local cache or directly from the network.

As you can see, Firestore is really powerful when it comes to realtime synchronization and offline capabilities. We haven’t even begun to see querying yet either, but don’t worry, it’s just up ahead.

Demo & Exercise

Let’s take a break to write some code.

- cd /3-cloud-firestore/start

- npm i

- npm run dev

- http://localhost:3000/1/realtime-streams

Once we’re done. We’ll get into querying.

Simple queries

Cloud Firestore is designed to scale up queries despite the number of documents it queries. A Firestore query has to search through 50 documents to only return 5, will roughly be the same as a query that searches through 5,000,000 that also only returns 5. These queries have to be fast every time not only because fast is good, but also because these queries have to work in realtime as well. Every query you can formulate in Firestore works with onSnapshot() for realtime streams and also works offline as well.

Cloud Firestore has two types of queries: simple and composite. Simple queries involve querying based on one field.

import { collection, query, where, limit, getFirestore } from 'firebase/firestore';

const db = getFirestore();

const expensesCol = collection(db, 'expenses');

const expensesQuery = query(

expensesCol,

where('cost', '>', 200),

limit(100),

);This query looks for expenses greater than $200 and returns the first 100. The only field that is used for the query is cost. The limit() function is just a restriction of the amount returned. Simple queries can have more than one where clause as well, as long as it’s on the same field.

Firestore comes with a whole set of operators that help you query through your data.

Equality Operators

Use the == operator for straightforward equality queries.

let expensesQuery = query(

expensesCol,

where('category', '==', 'food'),

limit(100)

);This query returns the first 100 expenses that have a category of 'food'. It’s still a simple query because the only field involved in the query is still cost. In Firestore you can also query within objects/maps.

let expensesQuery = query(

expensesCol,

where('user.city', '==', 'Maputo'),

limit(100)

);The “dot” notation allows you to drill into an object/map, this works up to about 20 nested objects deep. Now this equality query may not look too exciting, so let’s spice it up a bit and look for multiple cities.

let expensesQuery = query(

expensesCol,

where('user.city', 'in', ['Maputo', 'Buenos Aires', 'Santiago']),

limit(100)

);You can query for multiple ranges on one field as well.

import { collection, query, where, limit, getFirestore } from 'firebase/firestore';

const db = getFirestore();

const expensesCol = collection(db, 'expenses');

const expensesQuery = query(

expensesCol,

where('cost', '>=', 200),

where('cost', '=<', 210),

limit(100),

);This query gets the first 100 expenses that are between 200 and 210. All of these queries help find data within equality ranges, but you can also do the opposite with inequality operators.

Inequality Operators

Firestore supports a != operator.

let expensesQuery = query(

expensesCol,

where('category', '!=', 'transportation'),

limit(30),

);This returns the first 30 expenses that do not have 'transportation' as a category. Going back to the user.city query, you can query for a set of users who are not in a city.

let expensesQuery = query(

expensesCol,

where('user.city', 'not-in', [

'Maputo',

'Buenos Aires',

'Santiago',

'Stockholm',

'San Francisco',

'Dubai',

]),

limit(100)

);This will exclude all these cities from the query. It’s worth mentioning that the not-in clause does come with some limitations, you can supply only 10 values.

Ordering

Another aspect of composite querying is ordering results with orderBy().

const expensesQuery = query(

expensesCol,

where('cost', '>=', 200),

where('cost', '<=', 210),

orderBy('cost', 'desc'),

limit(100),

);In this example we’re querying for expenses that cost between 200 and 210. By using orderBy() we’re ordering the result set returned by cost and sorting the results in a descending order. This means the results will start at 210 and move down towards 200.

Composite Queries

Firestore will allow you to query based on two fields and return them just as fast as ever.

const expensesQuery = query(

expensesCol,

where('cost', '>', 200),

where('cost', '<', 210),

where('category', 'in', ['fun', 'food', 'kids']),

limit(100),

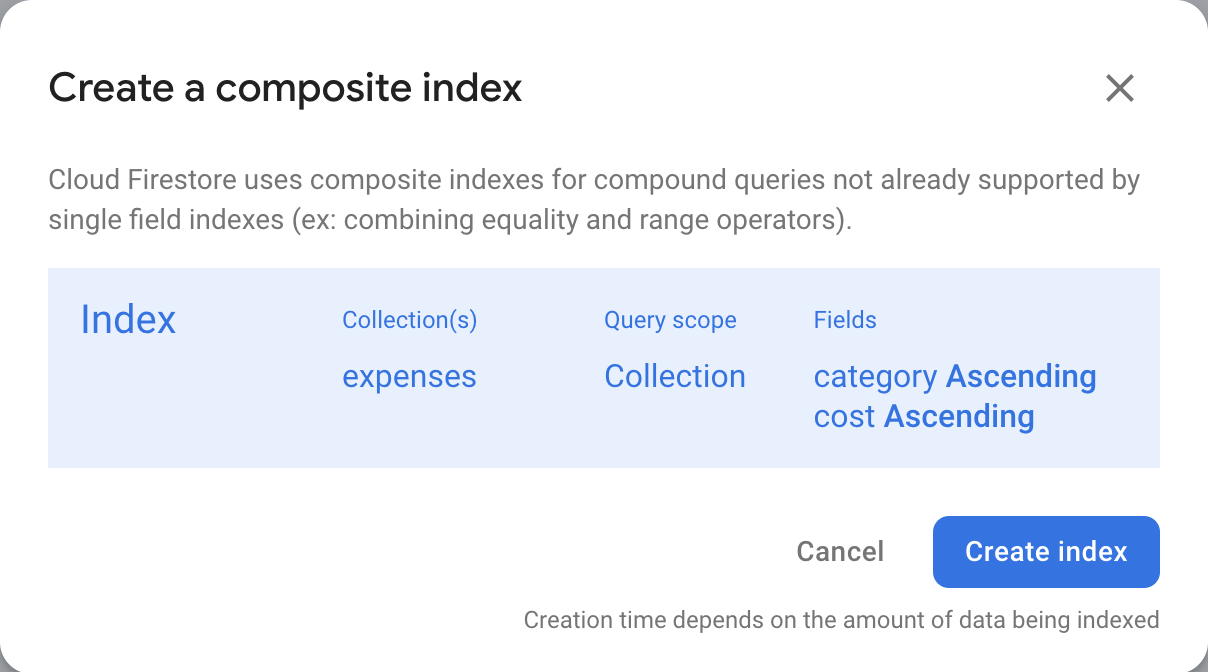

);However, there’s a catch. You need to explicity ask Firestore to create an index for this kind of query. Fortunately these indexes can be automatically created for you. When you run a composite query that doesn’t have an index created we’ll log out a link to the browser console for you to click on and then create a new index.

If you’re using the Emulator, you can execute composite quries without needing to create an index. But what’s an index anyway? And why do you need to ask Firestore to create them?

Indexes

In Firestore the time it takes to run a query is proportional to the number of results you get back, not the number of documents you’re searching through. How exactly does that? Well, that’s through the magic of indexing.

Whenever you create a document in the database, Cloud Firestore creates an index for every field in that document. An index is a sorted list of all the values in the field that are being indexed. An index stores the value and the id of the document in the database. This makes it fast and easy to query on a single field.

However, what about two fields? Each field has an index and its sorted by its own values, so they can’t be queried together.

Instead we explicitly ask Firestore to create a new index that is based on these two fields and with their values properly sorted.

This is called a composite index and it’s what enables you to query beyond one field in Firestore. You might be thinking at this point: “Why doesn’t Firestore automatically create composite indexes for every document?” The problem there is that there are far too many possible combinations when it comes to composite indexing. A document of 20 fields would create 6,000,000,000,000,000 different combinations.

Demo

Demo time! Let’s write some queries! Back the same

- cd /3-cloud-firestore/start

- npm i

- npm run dev

- http://localhost:3000/2/foundational-querying

Now let’s start looking into how Cloud Firestore handles arrays.

Array queries

Arrays in a realtime system can be pretty tricky. Array indexes are numeric and when data is being updated on the fly it really can shift things around and make them unpredictable. Firestore has a few conveniences in place to make dealing with arrays a lot easier.

Right now in our expenses collection, each document has a category field that is assigned to one string. But what if users wanted to be able to tag an expense with multiple categories? What would you do in that case? You could create a map and use its keys as the category names.

The document would look like this:

{

categories: {

food: true,

fun: true

}

}And the query would be a little awkward as well.

// don't do this!

const expenseQuery = query(

expensesCol,

where('categories.fun', '==', true),

where('categories.food', '==' true),

);I mean this works, but it’s not great. Instead we can use arrays.

{

categories: ['fun', 'food']

}In Firestore we have special queries for arrays.

array-contains

The array-contains operator allows you to query for documents using the values within an array.

const expenseQuery = query(

expensesCol,

where('categories', 'array-contains', 'fun'),

limit(10),

);This query will return expenses which contain the category of 'fun'. This is great when you have a use case for AND style queries. But if you need to find a document with more than one value, you need an OR style query.

array-contains-any

Using array-contains-any you can find documents by multiple OR values in an array.

expensesQuery = query(

expensesCol,

where('categories', 'array-contains-any', ['fun', 'kids']),

limit(25),

);The result of this query will return expenses that contain the category of 'fun' or 'kids'. You might end up getting back an expense tagged as 'kids' and ‘transportation’, maybe 'fun' and ‘food’, or in some cases you’ll get 'fun' and 'kids' if that pair exists.

Demo

Let’s dive back into the code

- cd /3-cloud-firestore/start

- npm i

- npm run dev

- http://localhost:3000/3/querying-arrays

Now this whole time we’ve been getting back an entire dataset or we’ve been limiting the result set. But how do you page through your data?

Range and Cursor queries

It’s unlikely that you’ll want to get all of your data back, that’s bad for bandwidth and the amount of reads you’ll be issuing. Instead we use Firestore’s set of range and cursoring functions for pagination.

We’ve seen limit() this entire time, it returns only the first specified number of results. However, you can also return the last specified number of results: with limitToLast()

expensesQuery = query(

expensesCol,

where('date' ,'>=', new Date('1/1/2022')),

orderBy('date'),

limitToLast(10),

);This query returns the last 10 expenses from the date range greater than 1/1/2022. If you wanted to keep expanding the set of results as a user scrolled or clicked a button you could be increasing the range in limitToLast(). Eventually, you would make it back to 1/1/2022.

However, that would keep pulling back more and more data with every scroll or click. Instead it would querying for a range of values and moving the range as you go through the data set. This is known as cursoring and Firestore comes with a set of useful cursor functions.

expensesQuery = query(

expensesCol,

orderBy('date'),

startAt(new Date('1/1/2022')),

limitToLast(10),

);This query returns the last 10 expenses from the date range greater than 1/1/2022, just like before, but now we have the ability to create a range with the startAt() function, now we can end the range with the endAt() function.

expensesQuery = query(

expensesCol,

orderBy('date'),

startAt(new Date('1/1/2022')),

endAt(new Date('2/1/2022')),

limitToLast(10),

);This query will display the last 10 expenses starting from 2/1/2022 moving back towards 1/1/2022. Given the size of the data set, it won’t go back to 1/1/2022 within 10 results. So how do we get continue to get back without increasing the limitToLast() size? Cursor functions can also accept document references as either starting or ending points.

expensesQuery = query(

expensesCol,

orderBy('date'),

startAt(new Date('1/1/2022')),

endAt(new Date('2/1/2022')),

limitToLast(10),

);

// Click to get the next 10 or something

const querySnap = await getDocs(expensesQuery);

const firstDoc = querySnap.docs.at(0);

expensesQuery = query(

expensesCol,

orderBy('date'),

startAt(new Date('1/1/2022')),

endBefore(firstDoc),

limitToLast(10),

);This one may look a little complicated, but let’s take a moment to step through what’s happening. We start by creating the same query as before. The last 10 expenses within 1/1/2022 to 2/1/2022. Then we retrieve the docs in the query. In this case let’s assume the user clicked on a button or scrolled to issue the query. After we have the documents, we’ll get the very first one .at(0) and use that to create a new query that ends just right before that document. The endBefore() cursor function knows to cut off the range just right before it sees that document. If we repeat this process we’ll eventually get back to the last 10 expenses in the full data set.

Demo & Exercise

Let’s get to the code.

- cd /3-cloud-firestore/start

- npm i

- npm run dev

- http://localhost:3000/4/ranges-cursoring

NoSQL and joins

This entire time we’ve only queried from one collection. I’m sure a lot of you SQL developers are asking: How do you join data from other collections?

The answer, just like anything in web development, is that it depends on your situation. This is another situation where it’s helpful to look at what you might be used to in the SQL world.

Normalization

A cornerstone of SQL is data normalization. Normalization seeks to ensure that data is not duplicated across the database. This is commonly done through the use of foreign keys. Each row has a column that corresponds to another record in another table.

-- Can I have the user data and all of their expenses data as well? kthx!

SELECT e.id, e.cost, e.date, u.uid, u.first, u.last

FROM tbl_expenses as e

INNER JOIN tbl_users as u ON e.uid = u.id

WHERE e.uid = 'david';In this case we have tbl_users and tbl_expenses. Each expense row has a uid column that corresponds to a record in the users table. Referencing the data in a foreign key keeps the data from being duplicated, and possibly inconsistent, throughout the database. But what it does do, is it requires a query to build the result set of data. A query is pretty much a question:

This computes a result set back with all the data needed. Each time we need to ask this question we’ll have to run this query, but we won’t have to duplicate the data needed. NoSQL is a bit different.

Denormalization

In NoSQL databases you rely less on queries and more straightforward read operations. Let’s remodel this the expenses app for a NoSQL database:

Here we have two collections, users are indexed using the uid key. When I say “indexed” I mean what key are we using to find the record? In this case we are using the uid key to find a specific user. Expenses are indexed using a generated expenseId key. If you look at expenses, it has the expense data but also the user data as well. So getting the data is easy as a single query.

let expensesQuery = query(

collection(firestore, 'expenses'),

where('user.uid', '==', 'david_123'),

);Now I can feel my ears burning which tells me that some of you out there are completely aghast to the data duplication going on. You might be saying “What if the user updates their name or other information! That data is going to be inconsistent!” Well, that’s true. With NoSQL databases you do need to update that user data in every expense record.

That’s a technique known as fanout. However, this isn’t as bad of a concept as you might think. Fanout works really well in the case where data isn’t often updated, much like a user’s name. It’s extremely fast to retrieve the data without having to calculate a complex query.

Fanout can be done behind the scenes, so the user can continue to use their app while the data is updating.

The denormalization spectrum

Now just because I can use fanout, it doesn’t mean I always have to. In reality, I would not use fanout in this data structure. This is a one-to-many data structure. One user, many expenses. I would get the logged in user with Firebase Authentication, then use their uid to get their profile data, and then get their expenses.

let userQuery = doc(firestore, `users/${auth.currentUser.uid}`);

let expensesQuery = query(

collection(firestore, 'expenses'),

where('user.uid', '==', auth.currentUser.uid)

);

// Issue a one-time read for the user

const userSnap = await getDoc(userQuery);

// Create a realtime listener for expenses

onSnapshot(expensesQuery, snapshot => {

console.log({

user: userSnap.data(),

expenses: snapshot.docs.map(d => d.data()),

});

});This situation works really well for many types of data structures and especially one-to-many relationships. Just because you’re using a NoSQL database doesn’t always mean you have to go full onboard the denormalization train. A lot of developers coming from SQL are worried that if they use a NoSQL database they’ll have to pre-compute all their queries and into structures and fan out every data update for the rest of their life. But that’s not the case.

Denormalization isn’t a rigid specification, it’s a spectrum. You decide how much data duplication is needed, if at all. While Firestore is not like a SQL database, it does have a sizable set of query features that help you find your right spot in this spectrum.

However, if I were in a scenario where I needed to query all expenses across all users: a many-to-one relationship. I would strongly consider a denormalized strategy with an embedded user object/map like shown above. Otherwise my options would be to issue a read to get the user for each and every expense. And while this isn’t as complicated as you think, how often is it that a user updates their profile information?

Hierarchy

Another thing we’ve done this entire time, is that we’ve only queried data from top level collections. In Firestore you can structure your data hierarchically. Collections contain documents, and documents can contain collections themselves, known as subcollections.

Why is the hierarchy important? Two main reasons:

- Many structures make sense in a hierarchy: think folders and files.

- Hierarchies are based on paths, which can reduce or simplify queries.

Let’s take a look at this expenses database structure. The expenses collection has an index of a generated key. To get a user’s expenses you’ll need to run a query based on the uid field. As we’ve learned so far, when you begin to query on more than one field you start to have to build composite indexes, which you only have a limited number of.

What if we didn’t have to build a query at all to get a user’s expenses? What if we could do it with a straightforward read? Well, it turns out we can if we use subcollections.

Once you have a user’s uid in hand all you’d have to do is read the expenses subcollection.

let expensesQuery = query(

collection(firestore, 'users/david_123/expenses')

);No where clause needed. This not only makes it easier to query a single user’s expenses, but it frees up a field for querying as well.

One thing to note: queries in Firestore are shallow. This means when you query a document, you only get the document’s data and not its subcollections.

Subcollections simplifies querying for all expenses from a single user. However, since queries are shallow, did we just lose the ability to query for all expenses across all users? Not quite, because Firestore has a special kind of query that handles this scenario.

Collection Group Queries

Whenver you have a common subcollection name is Firestore, you can create an index for a special kind of query called a Collection Group Query.

In this case, each user document has a subcollection named expenses. Using the Firestore Console or just by clicking on a link, you can create an index and you’ll be able to query across all expenses.

let expenseGroup = collectionGroup(firestore, 'expenses');

expensesQuery = query(

expenseGroup,

where('cost', '>', 200),

where('cost', '<', 210),

where('categories', 'array-contains-any', ['food']),

);Now we have the best of both worlds. We can query across single users and we can query across all expenses.

Demo

Time for another demo!

- cd /3-cloud-firestore/start

- npm i

- npm run dev

- http://localhost:3000/5/collection-group-queries

Atomicity

One of the most important aspects of a database is being able to handle multiple operations in an all or nothing fashion. If one operation fails, rollback the entire process. This concept is known as atomicity.

In Firestore you can achieve atomicity through two but different ways: batched writes and transactions.

Batched Write

A Batched Write allows you to store an entire set of set, update, or delete operations into a single “batch” and them “commit” these operations.

import { writeBatch, doc, collection, serverTimestamp } from "firebase/firestore";

let batch = writeBatch(firestore);

// batch.set(), batch.update(), batch.delete()

// batch.commit()If even one operation fails the entire batch won’t go through.

import { writeBatch, doc, collection, serverTimestamp } from "firebase/firestore";

let batch = writeBatch(firestore);

let expensesCol = collection(firestore, 'users/david_123/expenses');

batch.set(doc(expensesCol), {

categories: ['food'],

cost: 123.23,

date: serverTimestamp(),

})

batch.update(doc(expensesCol, 'i-know-this-id'), {

categories: ['transportation', 'fun'],

})

batch.delete(doc(expensesCol, 'i-know-another-id'));

try {

await batch.commit();

} catch(error) {

// was there a problem? if so, roll it all back

}

// If not, we're done!A good usecase for Batched Writes are for when you are updating denormalized data across the database. If you aren’t able to successfully update everything in one go, you likely want to roll back and try again.

One thing to note is that Batched Writes have a limit of 500 documents per batch. If you need to update more than 500 documents at time you’ll need to create multiple batches. This does mean you could be in a state where some batches succeed and some fail. For these multi-batch situations it’s best to execute them using our server libraries. In general though, updating data over a period of time is a common practice many NoSQL databases.

Batched Writes are good for atomic processess, but they are only good for updating data without caring about the existing data in place. They are an overwrite style operation and they have no knowledge of the given set of data. In fact, if you needed to know the current state of data you’d have to read the data first and then update it via a Batched Write.

The problem there is that the read isn’t an atomic operation. That data could be out of date well before the batch commits, which could lead to all sorts of inconsistent states in your database. This is especially problematic for games or systems that need rules followed in certain order. For those situations, you can use transactions.

Transactions

Transactions allow you to run multiple operations in an atomic process including the access to reading data. This allows you to do important things in order, like update scores, and other process based data. This keeps users or events from going “out of turn.”

In many databases, transactions will lock the entity until the transaction is completed. The Firestore client libraries want to avoid locking a document. Clients are often unpredictable in their network state, imagine if a client locked a document and then went offline.

Instead of locking, Firestore will retry the transaction if something has changed. This is known as optimistic concurrency control, which will make you sound very fancy to say at parties.

import { runTransaction } from "firebase/firestore";

const pointsAwarded = // get from web app;

try {

await runTransaction(firestore, async (transaction) => {

const gameDoc = await transaction.get(gameRef);

if (!gameDoc.exists()) {

throw "Document does not exist!";

}

const data = gameDoc.data();

// Add to the score state

const score = data.score + pointsAwarded;

// Run the transaction

transaction.update(gameDoc, { score });

});

console.log('Transaction successfully committed!');

} catch (e) {

console.log('Transaction failed: ', e);

}In this example we’re getting new points awarded from a game. The transaction will run and attempt to update the new score. If the score is updated before this transaction runs, the transaction will try to run again to keep the state correct.

With transactions it’s important to follow a process:

- Read first - Get the state you need to update

- Update state - Perform the business logic (e.g. update game state)

- First attempt - Then a write is attempted and will succeed if the data is up to date.

- Double checking - Firestore looks to ensure that nothing indeed has changed from the first reed.

- Something change? - If data has changed from the first read, the transaction is re-tried.

Since transactions can retry, they can act a little funny. First of all, don’t modifiy any application or UI state within a transaction. This can lead to some seriously confusing bugs within your app because they will run more than once when a transaction is retried. If you want to open a <dialog>, don’t do it within the transaction, wait for the transaction to complete.

try {

await runTransaction(firestore, async (transaction) => {

// Do your transaction stuff

});

// Only after the promise has resolved

successDialog.open();

} catch (error) {

}Secondly, transactions will fail when an app goes offline, which is a good thing. Transactions are based off having the most up to date read, and that can’t happen while you’re offline.

Authentication and security

The database is still not secure, any user can read, write, update, or delete anything they want from the database. Like I’ve said before, the fix is security rules, however before we can get to writing these rules we have to cover our basis with authentication.